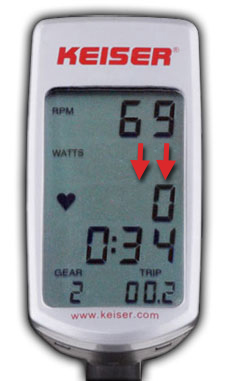

I coached one of the last weeks of Cycling Fusion”™s winter training program with a focus on developing muscular strength. The indoor ride consisted of a 15-minute warm-up, 2 openers (short, high intensity efforts) and then 4 climbing strength intervals. The goal of the intervals was to sustain the maximum load (resistance) while maintaining a slower cadence for 3 minutes. Although I told the riders that the climbing cadences for all of the efforts were between 60 and 70 RPM, I failed to stress the importance of this leg speed for achieving the desired result — strength. I also failed to alert the class that their power output would be less than what they were accustomed (they were riding on Keiser M3 bikes).

I coached one of the last weeks of Cycling Fusion”™s winter training program with a focus on developing muscular strength. The indoor ride consisted of a 15-minute warm-up, 2 openers (short, high intensity efforts) and then 4 climbing strength intervals. The goal of the intervals was to sustain the maximum load (resistance) while maintaining a slower cadence for 3 minutes. Although I told the riders that the climbing cadences for all of the efforts were between 60 and 70 RPM, I failed to stress the importance of this leg speed for achieving the desired result — strength. I also failed to alert the class that their power output would be less than what they were accustomed (they were riding on Keiser M3 bikes).

As we started to tick off the intervals, I observed the cadences of many of the riders increasing noticeably above what was indicated. As usual, I had the music tempo set to the desired leg speed for each climb. As riders were cooling down after the last interval, I walked around the room to chat and see how different people did. It was interesting to note that many of the riders increased their power (watts) during each climb. Although in almost all circumstances this would have been a good thing, in this case it was not.

Now keep in mind that this group of riders was used to training with power and was also used to seeing a certain (higher) power number when climbing. In addition, they were used to climbing at tempos closer to 70-80 RPM. So when I asked them to climb at a leg speed of 60 RPM, they immediately noticed a lower power number. They associated this lower power output as “not good” and thus FIXED it by backing off some resistance and increasing their cadence. Were they wrong in doing this? Well, in a general sense, no. It actually shows they understand the impact of cadence (velocity) on power output. However, in this case, the focus was on developing muscular strength which demands an emphasis on workload and not power output. The goal was to apply maximum force (stress) to the muscles of the legs for the entire 3 minutes. So during this workout, it was more important to target a slower (60 RPM) leg speed in order to maximize strength development.

SIDE NOTE: Having power meters during drills like this are still very important. Even though we are not going to expect the highest watts, we do want to make sure we are maintaining a consistent power output for each interval. This is one of the ways power is such a valuable tool. If we only have a heart rate monitor, we may observe the same or higher heart rates for each of the 4 climbing efforts. This only shows what the effort is costing our body and not how much is being produced. The addition of power allows us to see if we are maintaining a constant power output for each effort or if our power is dropping even though our heart rate remains the same or increases.

So if you are designing a class that focuses on developing leg strength, avoid the error I made and emphasis the importance of a sustainable 60-70 RPM cadence. I would also encourage the use of music that matches the desired leg speed so riders can feel the pulse. Music at 60 RPM (or 120 RPM/BPM) is usually the easiest to find since dance music is often at this tempo. And, as always, make sure your riders maintain good form and are instructed to work at their own pace particularly if they are nursing leg, back or neck injuries.

Ride Strong!

Originally posted 2011-05-19 05:00:17.

- Make Recovery Work - July 23, 2024

- The Effects of Cadence (Part 3) Power Output or Strength Development - July 17, 2024

- Don't Touch My Drivetrain! - June 14, 2024

Hi Tom,

I am excited to report that many of my riders are able to maintain 90-100+RPMs during class! We have been working on this higher cadence for quite some time now (one year) and now some of them ‘get it’! It is exciting to see this change from being ‘gear mashers’ to a more efficient and economical leg speed. Beautiful to see!!!! 😀

Old habits die hard and for some, gear mashing is still a favorite way to ride (even though some form is lost – while seated it looks like: hunched over/head down/jerky bobbing up and down upper bodies – at 60 or slightly less cadence).

How do you get them to make a change from this? We still do not have the luxury of meters that show HR, Cadence or Watts at many of the locations (except one – everything above minus the Watts) so we are still in the dinosaur age 🙁

It’s frustrating because I am soo soo ready to move on…