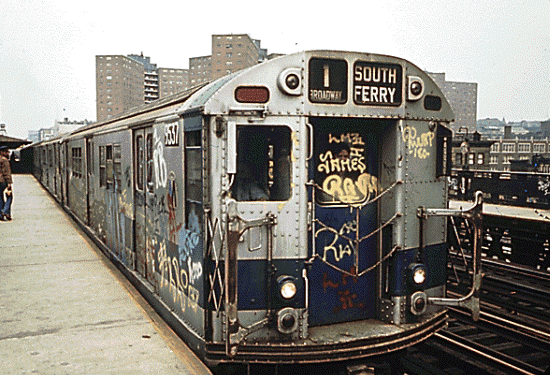

John rode the #1 NYC subway train last week and it doesn't look like this today 🙂

Giving nutrition talks in many locations lets me meet interesting people. After a recent presentation, a man came up afterward to tell me about his doctoral research.

Dull, you think? Hardly. The man is working on a program for juvenile offenders that teaches them about good nutrition. His premise is that getting them to make good decisions about food helps them make better choices in life.

How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference

I was instantly reminded of Malcolm Gladwell”™s book The Tipping Point. Gladwell describes the turnaround of the high crime rate in New York.

In the mid-1980s, violent crime in NYC was at a peak. Two criminologists, Wilson & Keller, theorized that crime is the inevitable result of disorder, and seemingly small displays of disorder invite serious crime by signaling neglect.

The NY Transit Authority hired Keller as a consultant. He convinced the key players to start the crime cleanup by cleaning graffiti from the subway trains. Some thought it was a foolish start because violence on the subway trains was so high.

But the repainting of trains was relentless. Even partially graffiti”™d subway cars were taken out of service until they”™d been cleaned. The message that someone was watching was clear, and it worked.

The theory was then applied to other small crimes, such as fare-skipping and minor property damage. By 1990, violent crime in NYC had dropped considerably.

So What Does This Have To Do With Sugar?

What if, instead of avoiding just the big stuff — like dessert — and letting little “tastes” slide by, you convinced your participants to start by eliminating the little tastes? Refusing that piece of a broken cookie, those two tiny M&Ms, that agave on their oatmeal? Small tastes that seem trivial, calorie-wise.

What good would that do? Well, sugar does affect brain chemistry and hormones, so small amounts can increase appetite and change food preferences — and not in a good way. A little can bring on cravings for sugar later that day or the next.

But What About Juvenile Offenders, Gladwell, and The Subway Trains?

I”™m also suggesting that strictly refusing small bits of sugar could help your participants develop a different mindset: “That”™s not food.”

What I know from decades of counseling dieting clients is they tend to think All-Or-Nothing. (“I ate cookies earlier, so I blew it. I”™ll have this chocolate cake tonight and start my “diet” tomorrow.”)

What if — this season — they get out in front of it?

If they relentlessly reject small samplings of sugar throughout the day (and the week), it could be easier to turn down dessert.

Yes, because of the brain chem thing. But also this: Why undo all that careful, healthy picky-ness by blowing it on a bowl of Rocky Road?

Dare To Start Small

We know holiday sugar will be around in both large and small portions.

Why not shun the tiny tastes of sugar that will be everywhere? See if that doesn”™t inspire better food choices throughout the day — and throughout the season. See if it doesn”™t re-frame sugar as the junk it is, rather than as food.

If this deceptively silly idea keeps your students from overdoing it on pumpkin pie, chocolate truffles, fudge, cheesecake, and everything else that will be temptingly available as the holidays go on, it could even be seen as their practice.

Imagine the inner glow of having a no-sugar practice.

Besides, if you convince your participants to try this, you will definitely be a Hero, like my friend who”™s working with juvenile offenders. What he”™s doing is brilliant. You could be, too.

I”™d love to hear how this Tipping Point approach works for your classes!

- New Year’s Resolutions: A Sugar Addict’s Survival Guide - April 15, 2024

- Motivation vs. Enthusiasm - October 12, 2023

- Why Exercise Shouldn’t Be Just One Thing - November 9, 2022