Coach Gino gets an assist from a professional statistician.

Let”™s Try This Another Way

After testing 14 different bikes, with 6 of them also being repeat tested at least twice, I was pretty disappointed to see the data I reported in our last blog. This was never meant to be just an academic exercise. This had pure practical motivation. I wanted to be able to do real and reasonable competition in class. I wanted to encourage more tantalizing trash talk among my most competitive riders. I wanted to let some of my “little old ladies” throw it down against some of the guys who think bigger is better. I needed the bikes to be on an even scale to do this in good conscience, and handicapping them against a reputable objectively measured power meter seemed like a no-brainer to do just that.

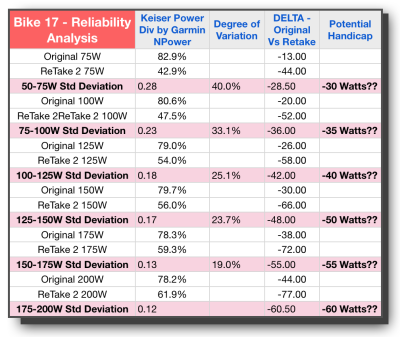

But alas, the numbers from my work up to this point lead me to a conclusion I simply had not anticipated; that each bike within itself may vary day to day with regards to what power it will display given the same force being applied. This was an assumption that myself and many other "defenders of calculated power" have held on to for these past 4 years or so - that it doesn't really matter if the power is accurate compared to what would be measured with a real power meter, as long as that power was consistent. In other words, we could know if our training was making us better or not by pre and post testing on the same bike. It would simply generate a relative value so we could know if we improved a lot, a little or not at all. Each year at Winter Training we would assign bikes so that we could be assured of this "fact". This was indeed the fundamental assumption that prompted the entire notion that a handicap could indeed be created, if we had a objective way to get at power simultaneous to seeing the bike's power display.

Unfortunately, as you could see from the numbers reported the last time, they varied so much within the same bike, from one testing episode to the next (even despite painfully recreating the same circumstances of a consistent rider, environment, time of day, method of execution and all the like), that this assumption was not true for at least 50% of the bikes. Undaunted by this surprisingly sad turn of events, I started to ask around for an available statistician that might be interested in this research. I wanted a more experienced extra set of eyes and less personally invested perspective so that they could let me know if I am doing something wrong. Was I measuring the wrong way, perhaps working with false assumptions, not controlling enough variables, etc. I didn”™t want to give up just yet — I had already invested too much time and energy.

3 More Bikes Tested, 3 Times Each

One of my regulars referred me to Sarah who is both a cyclist and teaches statistics at a nearby university. We met a couple of times to discuss what I had done so far, and she spent some time and thought on the issue, and created a new protocol. We would focus on just 3 bikes, took them out of commission so no one else would ride them, made sure she conducted/directed me as I rode/tested each bike. These trials would be done on three different days, in random order as generated from a random table of numbers. This video takes us through one of those three sessions.

In the next blog post, we will discuss the results of these 9 trials.

Indoor Cycling Power Accuracy & Validation Research from Cycling Fusion on Vimeo.

Originally posted 2014-02-19 03:04:24.

- Me & My Big Mouth - April 18, 2024

- Indoor Cycling Power Research #7: Good News, Bad News - August 16, 2023

- Blog Post #10 Baseline& Performance Testing - June 29, 2023